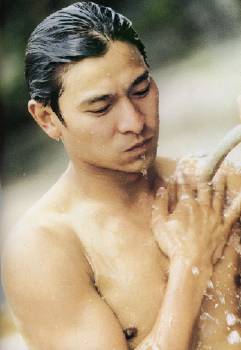

Not Andy (Yuen Biao)

Everything.

Long, long ago, in a Midlands far, far away, a back street Leicester cinema made its money alternating soft porn with poorly dubbed kung-fu kick flicks. And good girls with principles never set foot over the threshold. This wasn't film, wasn't art, or entertainment, this was only pulp, hidden in the darkness like a copy of Playboy under the covers. This wasn't for me, or any other woman. Remember that. Remember that association. Nothing exists in a vacuum. Conspiracies are everywhere. There is no escape from the patriarchy. I thought, back then, that the barrier that kept me out was one of age, or discrimination, or just my own better taste. I thought the kung fu movie was too violent, or too boring, or just plain too bad.

Too bad, honey. You missed out big time there. The Leicester Lighthouse knew a thing or two. What the girl can't see, the girl won't lose sleep over. Hong Kong cinema, all of it, is a boys' own playground. Even now, the dual strands of Hong Kong cinema literacy are barbed and twisted against us. The output is relentlessly male-targeted, from the sentimental boys'-bonding bloodshed melodrama of John Woo, via the low-budget, soft-porn, tit flicks, to the masturbatory, self-congratulatory misogynism of arthouse hero, Wong Kar-Wei. This is red-blooded, macho, beefcake-on-the bone-land. Girls keep out. You won't understand.

And if you do, we won't like it. I should have remembered all along that the Lighthouse was a porn cinema.

Not Andy (Yuen Biao)

Pull the plug on Titanic, strip Sharpe of his shiny black boots, and buy Sean Connery a bath-chair. The most beautiful man is the world isn't di Caprio, or even David Sylvian. He's a thirty-something action star and singer from Hong Kong, named Andy Lau Tak-Wah. Alain Delon on ecstasy, a lean, mean, honed clean gun-toting angel, with an oiled velvet singing voice, and a body to make you dream. And he's not on his own. In Hong Kong, they churn them out by the bakers' dozen. All through the seventies and eighties, it was the best-kept male secret in the Western world. Hong Kong action cinema is the bad girl's dreamland in Dolby and Technicolor. One night with Andy will ruin you for Tom Cruise forever. Here is the place where men are fit, and fast, and beautiful, and don't care how they touch each other. This is the celluloid heaven, where boys in wet silk smoulder at their women, and each other, and never stop to worry that the next stunt might just hurt. In Hollywood, carefully made-up Ken dolls pose before blue-screen, and worry about their manicure. Action stars are overbuilt, wooden performers, whose careers rest not on what they do, but on what they did before they entered the sound stage. Who cares that Steven Seagal was a Navy SEAL, or Van Damme was European karate champion? Hollywood puts big red ring fences round its action movies, and panders to frail male egos with press-packs, and massaged histories.

The most elegant of Caucasian action stars, the charming Richard Norton, has never been much of a success in the West. We don't want action stars who appeal to the girls. Girls want romance, as any fool knows. It's a benchmark of dating. Bore him with that Julia Roberts weepie, then let him bore you with the latest piece of Seagal action. It has to be boring. Otherwise the women might just discover the secret which the Boots advertising crew are latching on to. Fit and beautiful men are more fun than the lazy slob you're with. It's no surprise that most major league action stars in the West are well into middle age, and showing it.

Go check out the b-list, girlfriend, and look for the films with the magic words 'Jackie Chan'. Jackie may be 44, but he still knows the secret. Women dream about heroes, too, and we like them taut and fit and hurting.

Hong Kong action cinema is the new female pornography. Maybe the guys have always known it, and that's why even now they try so hard to keep us out. Just a few weeks ago, the check-out chap in the Cardiff Virgin megastore tried to tell me that I didn't want to buy that Hong Kong stuff, that it was really for the boys. But I'm old enough, now, not to fear the dark and the raincoats. Old enough to know what I like. Behind the machismo of the labels, the pictures of Chinese women in leather and bullet belts, is a genre which worships the male body -- and shows the object of worship in the clearest possible light. Schwarzenegger was never as dedicated as this to the cult of the body beautiful. In the 1960s, director Chang Cheh purposely constructed a genre which could showcase the very finest, leanest, meanest men on the block. The semi-erotic torture sequences in Lethal Weapon or The Ipcress File and their ilk are not even outside contenders by comparison, and the buddiest of buddy movies loses all its charge. In the Hong Kong genre, there are few gimmicks, few stunt doubles, and few compromises. The blood-and-gangster-melodramas of John Woo pack the same load of passionate tension as the best Joan Crawford melodramas of the 1940s and 1950s, but it's Crawford on speed, with emotion and intensity as burning hot as the bullets which riddle the plot. The classic era kick flicks of Chang Cheh and Yuen Woo-Ping, and Liu Chia Liang contain training sequences whose sadism can take your breath away. The action comedies of Jackie Chan, and Corey Yuen Kwai, and Sammo Hung Kam-Bo are physical poetry, where motion transcends, expands, defies the conventions of words. The fantasy and science fiction pictures of Tsui Hark, Ching Siu Tung and Johnny To reassign to the genre the adult themes which in the West are permitted only in the very best of the written works. The boundary between action and romance, boy toy and chick flick, is rubbed out, elided, forgotten.

Jackie Chan & Yuen Biao

And the men are beautiful, almost all of them. Rotund Sammo Hung Kam-Bo defies conventional wisdom about fitness and fatness. He's 200 lbs of dynamite. Jackie Chan, with his bandy legs and broken nose, has the most engaging screen persona in the world, an irresistible everyman. Gun-toting Chow Yun-Fat has the same smooth charm that made a pin-up of Cary Grant, and he's sharper, and defter. Arthouse darling Leslie Cheung Kwok-Wing has perfect pretty rentboy looks. And there are many, many more: elegant Ti Lung, tall and deadly Dick Ti Wei, Simon Yam Tat-Hwa, Danny Lee Sau-Yin, the two Tony Leungs (Leung Ka-Fei and Leung Chiu-Wei), Donnie Yen Chi-Tan, Jet Lee Lian-Jie, Leon Lai-Ming, Aaron Kwok Fu-Sing, Adam Cheng Siu-Chow, Stephen Chow Sing-Chi. And almost all of them are more gifted actors than the current crop of Hollywood stars. One or two, I'd pass on to girlfriends, if offered the gift of a night, but only because of favours owed. I'd keep most of them for myself. There's nothing on display in Hollywood to touch the magic here. There is something in this red-hot knife-edge world for everywoman.

Including me. My heart speeds up for several named above, but fastest of all for one I haven't named. The sexiest man in the world outside Cambridge is a forty-one year-old father of four, with chronic ankle trouble, and crooked teeth. He uses the screen name Yuen Biao. He's the best gymnast on film outside the sporting world. He's as fearless as Jackie Chan, as talented a dramatic actor as Zhang Fengyi, and at his peak, he could kick an opponent with his back to same, over his own shoulder. And he's not afraid to bleed. The training sequences in his debut film, Knockabout, take screen voyeurism to a new level of sado-masochism. The fetishism of the athletic, young, suffering, male form cuts to the bone, almost literally. Training/perfecting/tormenting of disciple by master requires utter submission. To teach him to turn backflips with legs perfectly straight, the master, played by the aforementioned Hung Kam-Bo, ties bamboo staves, sharpened at each end, to the backs of Ah Biao's calves. The blood is real, and so is the pain. In film after film, male suffering is iconised, packaged, and delivered to the viewer in slim, fit, beautiful packages. (It's usually male, but there are a few exceptions. In Legend of the Drunken Master Simon Yuen Siu-Tien metes out similar torment to Sharon Yeung Pan-Pan.) A fair percentage of Hong Kong film performers began their careers in Chinese opera, a medium that places a premium upon physicality. Expressiveness of eye is trained by hours sitting in darkened rooms following flickering candle flames.

Yuen Biao again

The Hong Kong cinema is a domain of burning glances, slash fan heaven, no doubt, when both objects are male. John Woo's The Killer explores obsession through small scale moments and large-scale shoot-outs, but the script is resonant as much in expression and motion as in words, until injury itself is sexualised, as the act of removing a bullet becomes less to do with healing than possession. In Sword Stained with Royal Blood, the insane Golden Snake Man is almost silent, conveying the intensity of his two guiding passions (revenge, and love for his lost wife) as much through what he does not say as what he does. Sword has an actor in common with The Killer, Danny Lee Sau-Yin, a master of the art of silent speaking. There is as much burn to his passive submission to the knife wielded by his screen wife, Elisabeth Lee Mei-Fung, as to his active invasion, with knife and gunpowder, of Chow Yun-Fat's bicep. In On the Run, Yuen Biao and Patricia Ha Man-Chik have no words at all to use to describe the chemistry which binds their characters. The script, focused, dark, intensely political, leaves no room for expressed romance. And yet it is there between the lines, a growing sexual tension rooted in violence, anger, and the allure of pain. The body, perfected, betrayed, broken, abused, exploited to its physical limits, lies at the heart of almost all the films of Jackie Chan, and the same intense objectification is refracted through most other films emanating from Hong Kong. Even the Westernised director Wong Kar-Wei does more with silence and motion than with words, and embodies (literally) his obsessions on screen in the pretty, narcissistic, frame of Leslie Cheung Kwok-Wing. The impact is instant, violent, physical, visceral, breathtaking in its extremes of parallel perfection and danger. Unsurpassed action queen Michelle Yeoh (Yeung Chi-King) broke her neck diving from a road bridge onto a moving lorry many feet below. She spent months in hospital, and then went straight back into the genre. The premium lies in the risk, and in the exultation of fitness.

Andy Lau

No Western action star ever maintains the same level of physical perfection for as long. The corporate world doesn't encourage it. Insurance companies lay down the law. Performers like Van Damme use doubles. Western audiences are trained to accept the blue screen, to wipe away any query about the suitability of 65-year-old Eastwood to guard the president, or sedentary Cruise to cling on to a train. Our pin-ups are carefully packaged, with the sweat created by make-up, and the reality brushed aside. They're no real competition for the average Western male on the street. The inevitable comparisons won't be too bad. That was blue-screen behind Geena Davies when she leapt from a window in the overrated Long Kiss Goodnight. Jackie Chan, who is afraid of heights, voluntarily fell three times from the top of a three-storey clock tower in Project A without benefit of mats, wires or pads. He survived the experience, but the out-take reel that ends the film shows you the price, as one take goes wrong, and Yuen Biao forgets his screen role to run into shot and help his co-star, who is also his 'opera-school big brother'. That's blue screen, too, behind Tom Cruise on the train in Mission Impossible. Yuen Biao doesn't do out-take reels, but admitted after the event that being dragged along the runway, and then up into the air by a plane for Righting Wrongs (aka Above the Law) had been somewhat scary. One of my friends is made uncomfortable by the whole Hong Kong genre. Human beings, he says, are simply not supposed to bend and move and contort like that. Not in the real world. It's a point I can see. But I have learned to love the fetishism, the perfection, the adrenaline rush.

Go East. The standards are higher, and you're encouraged to look. Ask for perfection, and passion, and pain. And never let them tell you that the action flick is a boys' own zone.

--Kari

Some recommended viewing, available in the UK:

Visit the Plokta News Network: News and comment for SF fandom