Do Artists Dream of Electric Shepherds?

LONDONERS are often called upon to justify the reasons for living in such a noisy, dirty, smelly place. It is traditional, when asked this question, to talk about how marvellous the museums and galleries are, and how splendid it is to be able to visit them on a whim. In practice, of course, the average Londoner visits a gallery about as often as they visit Mars.

But over the last few months, I have been visiting galleries. I didn't turn my maternity leave into a cultural improvement programme deliberately. It started off with a chance visit to the Natural History Museum, with Jo and Sasha Walton, as detailed in the previous Plokta. Then I found myself at the Royal Albert Hall, with a couple of hours to kill, and thought I'd visit the V&A. Several other galleries soon followed.

Mike, Caroline and I decided to visit the William Blake exhibition at the Tate. Once there, we discovered that as well as seeing Blake we could also see the Turner prize exhibition for a further pound. Americans amongst you may not already be aware of the Turner Prize. It is Britain's pre-eminent modern art award and as such is generally awarded for the body of artwork that Turner would have most despised. This year's award was particularly controversial because two of the nominees were artists. By which I mean that they actually painted pictures on paper. Quite nice pictures some of them.

But the artist whose work I was particularly keen to see was Glenn Brown. He is notable for producing artwork that copies other pictures. Some of his sources are science fiction paintings, and others have science fictional elements. My particular favourite, populist that I am, was a huge canvas entitled The Loves Of Shepherds 2000 (after Tony Roberts). It depicts a spaceship flying in front of a planet, and fills an entire wall of the Tate. Glenn Brown works in meticulously fine detail, and produces a smooth, glossy finish to the painting. The result is that the ship jumps out at you with terrific three dimensionality. I loved it. It must be rare for the Tate to exhibit a painting that would not, in content at least, be out of place at the Novacon artshow.

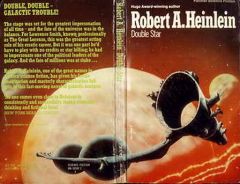

The following day, the storm broke. "Artist accused of plagiarism," said the headlines. It turned out that the particular picture I liked so well—"mysteriously entitled The Loves of Shepherds", explained the Times' art critic—was copied from the cover of the 1974 Pan Edition of Double Star. It turned out that every cabal member had a copy of the picture upstairs in their book stacks. We got them out and peered at them. The paintings were nothing like, as you can clearly see from the copies below.

|

|

| Second rate hackwork | Great hope of British art |

They're not much alike, in fact. Sure, the structure of the ship is the same. But Brown has changed the scale, added vast amounts of detail to the ship, and totally changed the planet. He could have used any ship, and any planet; the precise choice is irrelevant. Except, of course, that it's not. But more of that later. Brown likens his technique to that of Fat Boy Slim; pulling forms, techniques and riffs from a wide range of art through the ages. The skiffy art equivalent of sampling, in fact.

We watched a video interview with Brown. He explained, "If [my paintings] were completely abstract people would take them very seriously and consider the colour, and the tonal quality of them and what it actually meant in a very soulful way. But you put a spaceship in there and everyone goes ‘ugh, it's low, it's pathetic, it means nothing, it's childish.' And I'm thinking, ‘hang on, do these narratives not mean anything?'"

They showed The Loves of

Shepherds, with a backing track of I Lost My Heart to a Starship

Trooper. We sighed at the predictability of art critics dealing with

science fiction. But then we discovered that Brown has actually painted a

picture called I Lost My Heart to a Starship Trooper; a copy of a

small child detailed from Rembrandt. The explanation was this small Flemish boy

might well have loved SF, but was never given the opportunity.

They showed The Loves of

Shepherds, with a backing track of I Lost My Heart to a Starship

Trooper. We sighed at the predictability of art critics dealing with

science fiction. But then we discovered that Brown has actually painted a

picture called I Lost My Heart to a Starship Trooper; a copy of a

small child detailed from Rembrandt. The explanation was this small Flemish boy

might well have loved SF, but was never given the opportunity.

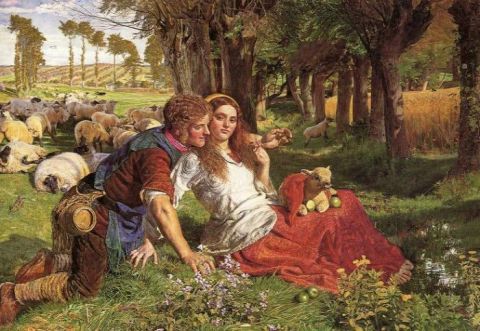

I feel that by writing about art, I'm going out on a limb. I'm not an artist, or an art critic. Surely art critics know much more about their field than I do? Well, maybe not. One recurring theme of the reportage on Brown's controversial picture was the title. "Why is it called The Loves of Shepherds?" asked the critics. They were mystified. But two minutes on the web gave me the answer. "The loves of shepherds" is a term of art describing pastorals—for example, the William Holman Hunt painting The Hireling Shepherd that features in Report on Probability A.

Pastorals are lyrical and hyper-coloured. The scenes they depict are pure fantasy; far removed from the harsh life of real shepherds. Their purpose was to provide a brief respite from the grind of early industrial society. By titling his huge panorama The Loves of Shepherds 2000, Brown's clear implication is that science fiction books and movies provide the equivalent escape from our world.

Picture of a shepherd looking

amorous

"Hello darling, that's a very sexy looking... sheep, you've got

there"

Similarly, nobody worked out that the choice of Double Star was deliberate. Although several writers suggested (much like Plokta correspondents) that it was a pleasing and accidental happenstance, Brown's work is layered with endless shades of meaning. I have no doubt that he chose to ape the cover of a book whose central motif is impersonation. In particular, Double Star asks many questions about the validity of copies, and of whether an impersonation can equal, or even surpass, the original. Meanwhile, Brown produced his huge painting working from the crappy reproduction of the paperback cover.

Certainly the Brown is a far better painting than the reproduction of the Roberts. But neither we, nor he, know what Tony Roberts' original painting looks like, only how it was interpreted by Pan.

Of course, the articles criticising The Loves of Shepherds reproduce the painting inadequately, as we have done. One of Brown's many levels of irony is that both his pictures, and those he's copying, are normally considered in reproduction. We don't normally have the opportunity to go and consider originals, to view paintings as they're meant to be seen. It's too late to view the Turner exhibition now, so the chances are you won't be able to see The Loves of Shepherds again. It was a private commission, and it will hang on the wall of some rich person. But I want it on my wall, no matter that I don't have a wall big enough. Or a house big enough, for that matter. And I wouldn't mind getting a reproduction of it, but I rejected the postcard. It's stupid to have this painting as a postcard, and besides, the colours are all wrong. It totally fails to provide the sense of solidity and overwhelming scale of the original.

Meanwhile, there are people out there considering this fabulous painting a plagiarism. They've seen nothing better than the postcard. "Sure, the colours are different," said one writer. "But when I fill in a colouring book, I don't claim it's my original." "I don't care how beautiful it is; it's still stealing someone else's idea," said another.

These people have no fire in their souls.

—Alison Scott

|

Previous Article |

Next Article |

![[Plokta Online]](../onlinelogo.jpg)